(PHOTO CREDIT: Andrew Gordon and Natali Chavez)

You are a first time filmmaker.

You are planning the climax of your first film, starring a brave, battle-hardened heroine who faces off against a terrifying, fire breathing dragon.

The scene, marked by immense tension and palpable danger, will represent the greatest culminating conflict in the narrative. The heroine’s armor, sword and face will shine with the piercingly bright light emitted by the dragon’s fiery breath. The fantastical castle she makes her last stand in will be bathed in a backdrop of darkness, creating a stark contrast that only furthers the viewer’s sense of suspense.

However, there are a few problems: you have a limited budget and only have your LA apartment to use for the set and the lighting.

Unfortunately, it is extremely difficult to replicate a medieval cobblestone castle background in your living room and the overhead fluorescent lights fail to capture the dark realism of the scene.

Without lighting equipment and a proper background, the mystical castle, the terrifying dragon, and the legendary heroine will be awash in the same dimensionless light and monotonous setting. Alongside the reflection of the dragon’s breath, the gnarled skin of the dragon, the heroine’s renowned sword, and the cobbled, textured bricks of the castle walls– all of these details of fantasy will be lost.

Or will it?

Challenges in Bringing Light To Stories

There are innumerable considerations to make when developing a film, in terms of budgeting, casting, filming, editing and coordinating sets. But amongst all of these responsibilities, what is the greatest challenge faced by most filmmakers?

“Over its 25-year history, ICT’s researchers have made several important contributions to the technical aspects of filmmaking, especially in the areas of photorealistic virtual actors and visual special effects,” said Andrew Gordon, a USC Viterbi research associate professor of computer science and director of Interactive Narrative Research at the USC Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT). “Many of the most challenging technical problems in filmmaking are about light.”

Lighting can constitute a nuanced struggle faced by numerous filmmakers even within Hollywood. Requiring high amounts of expertise, space, and finances, lighting can serve as a fundamental challenge when creating films.

Critical scenes may have to be re-filmed due to technical errors, climatic conditions, or shifting light sources, posing a significant detriment to filmmakers. Re-filming can require extensive costs, labor, and time for beginning filmmakers who may lack needed resources.

Researchers at the USC Institute for Creative Technologies are exploring how recent advances in AI-based image processing can be used by aspiring filmmakers facing this exact problem.

Relighting Shots with the Help of AI

Reducing the need for traditional lighting equipment, Gordon and Natali Chavez, a professional actress, filmmaker, Ph.D. candidate at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, and research scholar in the Narrative Group at USC ICT, have devised an innovative workflow for changing the lighting environment in post-production, after a scene has been filmed.

But how can you add realistic lighting to a video you already filmed without adding a filter or wash of color over the whole video?

Their solution is to use recent AI models to infer the material properties of each video frame so that it can be relit using synthetic lights in 3D modeling software.

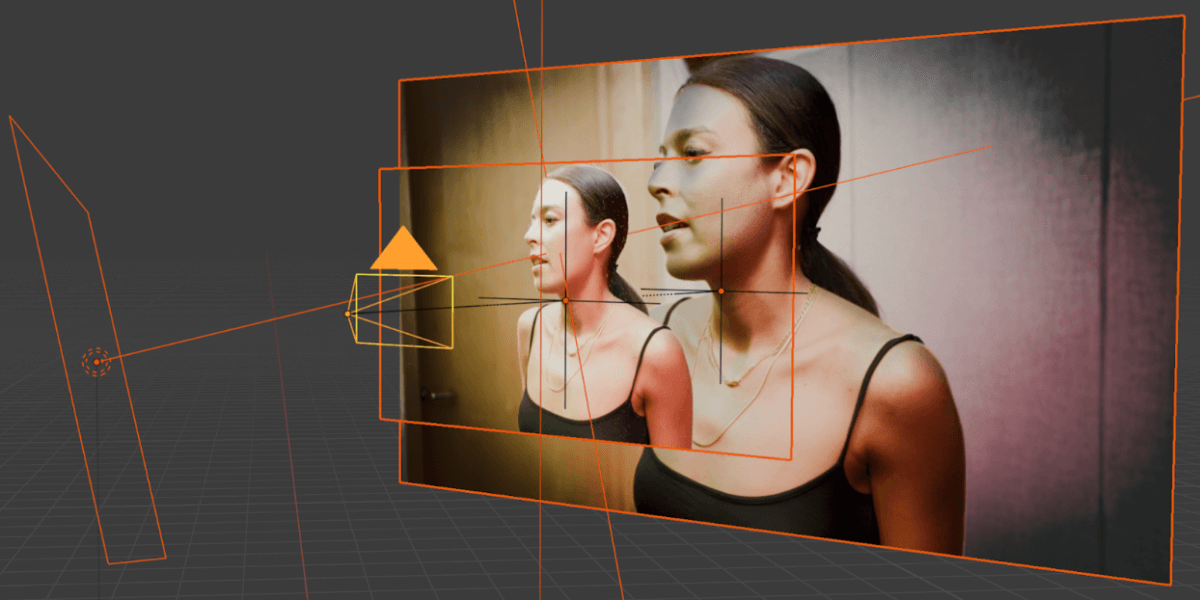

For example, a clip of an actress filmed in a neutrally lit setting is processed by different AI models to infer the metric depth and surface normal for each image pixel, as well as a foreground mask to separate the actress and the background into two image planes. These two planes, along with their inferred material properties, are then imported into 3D modeling software known as Blender, and scaled and positioned in 3D space such that they completely fill the viewport of a virtual camera. With their inferred material properties, these planes react to synthetic lights as if they were 3D objects, allowing filmmakers to design creative new lighting environments in software in post-production.

Material properties of each frame in a live-action are inferred using a variety of recent AI image-processing models. (PHOTO CREDIT: Andrew Gordon and Natali Chavez)

“We call it a ‘camera-aligned material plane.’ By scaling and aligning these 2D planes correctly to the virtual camera, the rendered images retain the same resolution as the original footage, but where each pixel is relit using synthetic lights in the 3D environment. The material properties assigned to these planes allows them to react to light as if they were 3D objects, allowing filmmakers the ability to experiment with various lighting conditions, or even to change out the background with an entirely different scene,” explained Gordon. Their software for importing camera-aligned material planes is available online as an open-source plugin for Blender.

The foreground and background of the original footage are imported into Blender as 2D planes with inferred material properties, where synthetic lights can be positioned in 3D space to relight the footage. By scaling and aligning the planes to a virtual camera (yellow pyramid, above), the relit footage retains the resolution of the source video when rendered. (PHOTO CREDIT: Andrew Gordon and Natali Chavez)

This workflow allows filmmakers to experiment with lighting in post-production. How might things look differently with a bright side-light to cast harsh shadows across the actress’s face? Would dim blue lighting create a better ambience for a more melancholic scene? Or how would it look if we replicated the signature lighting styles of iconic directors of the past?

These considerations are already an inherent aspect of creating animated 3D films. This new AI-assisted workflow opens up similar opportunities to manipulate lighting environments in live-action filmmaking.

Accessibility and Support for Aspiring Filmmakers

Although fully AI-generated filmmaking continues to show promise, Gordon sees this type of technology instead as AI-assistance to the traditional film production process. “This method of production still requires great writing, directing, acting, audio-visual capture, and editing, but the costs and logistics of lighting performances are greatly reduced by moving them into the digital domain.”

Chavez found a uniquely personal connection to the software that she is collectively developing with Gordon. As both a researcher and a passionate filmmaker, Chavez can attest to the importance of creating accessible resources for beginning filmmakers.

“I find it incredibly useful for emerging filmmakers like myself,” said Chavez. “It’s essential for artists to be able to express their vision, even when working with a minimal budget.”

Chavez’s experimental film ‘Can I have a Minute?’ was produced with the framework of USC ICT’s interactive narrative research, using minimal crew as a proof of concept for this innovative production workflow.

In addition to her short film, Chavez is investigating the correlation between emotions and brain activity during acting performances. She is currently analyzing EEG data she collected from actors trained in the Stanislavski method, aiming to advance the understanding of authentic emotional expression in media and enhance the realism of virtual actors. Her study, titled ‘Assessing Emotion–Brain Activity Correlation During Actor Performance,’ is part of her PhD research and Fulbright scholarship at ICT’s MxR Lab.

A preview shot from Natali Chavez’s new experimental film ‘Can I Have a Minute?’, featuring an edited background and digitally simulated light to match the surrounding environment. (PHOTO CREDIT: Andrew Gordon and Natali Chavez)

Gordon and Chavez continue to look for opportunities to improve their virtual production workflow. This includes incorporating new AI models to infer material properties in videos, and streamlining the process of camera tracking so that real-world camera motions can be easily replicated in 3D virtual environments.

For Gordon and Chavez, the most important next step is to get these new tools into the hands of aspiring filmmakers, especially USC students in the School of Cinematic Arts (SCA). As Gordon expresses, “I’m excited to see what small teams are able to do with these new AI-assisted filmmaking tools, especially where they can remove some of the financial and logistical barriers to making big pictures. That’s been the motto in our research: small teams, big pictures.”

Published on May 27th, 2025

Last updated on May 27th, 2025